The Trolley Dilemma in Chinese Philosophy

Would Confucius Pull the Lever?

Word of the week: 电车难题 (diàn chē nán tí)

Meaning: Trolley Problem

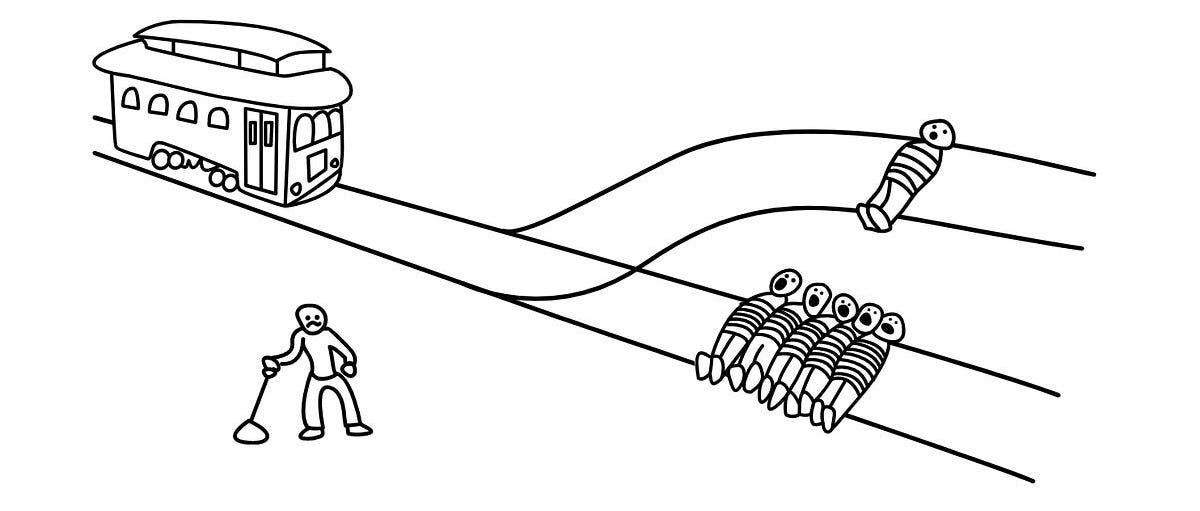

The Trolley Problem is a widely discussed moral dilemma around the world. Would you pull a lever to save five people by sacrificing one, or would you do nothing and let the trolley kill five instead of one?

Let’s read a great article by 地产三哥 explaining how a Buddhist, a Confucianist, and a Taoist could react to this situation. It is a rather advanced text with a lot of philosophical and historical vocabulary. If you like abstract thinking, today’s lesson is for you!

一辆有轨电车轰轰烈的行驶过来,前面是岔道口。左边的轨道上绑着一个人,右边的轨道上绑着一群人。岔道口有个扳道工,电车向左还是向右行驶,方向取决于扳道工。扳道工应该如何抉择?是碾压一个,还是碾压一群?

以上是简化版的“电车难题”。只是臆想一下,在中国传统的释、儒、道的体系中,扳道工会怎么选择?

有轨电车 (yǒu guǐ diàn chē) – tram / trolley (literally "rail-guided electric vehicle")

轰轰烈烈 (hōng hōng liè liè) – with a loud rumble, vigorous and intense

行驶 (xíng shǐ) – to travel, to move (of a vehicle)

岔道口 (chà dào kǒu) – fork in the road, junction

绑着 (bǎng zhe) – tied up

扳道工 (bān dào gōng) – switchman (railway worker who controls the track switch)

碾压 (niǎn yà) – to crush / to run over

臆想 (yì xiǎng) – to imagine, to fantasize

释 (shì) - here: a short for 佛教 (fó jiào) — Buddhism

A trolley is rumbling down the track, approaching a junction. On the left track, one person is tied up; on the right track, a group of people is tied up. There is a switchman at the junction, and the direction the trolley takes—left or right—depends on the switchman. How should the switchman choose? Should they run over one person or a group of people?

The above is a simplified version of the “Trolley Problem.” Just imagine: within the traditional Chinese systems of Buddhism, Confucianism, and Daoism, how would the switchman choose?

一、扳道工是佛教徒

《佛说大方广善巧方便经·卷第四》*中有个故事:

阿罗汉到海外去弘法,跟一些商人一起坐船。船上有五百商人,其中有一个人起了恶念,想把同伴都杀掉,独吞所有的财物。阿罗汉能通人心,知道了这个人的念头非常强烈,还没办法劝导。于是,阿罗汉选择了开杀戒,把他杀掉,救了所有人。

阿罗汉 (ā luó hàn) – arhat (a person who has reached enlightenment in Theravāda Buddhism)

弘法 (hóng fǎ) – to spread Buddhist teachings / the dharma

恶念 (è niàn) – evil thought, malicious intention

独吞 (dú tūn) – to monopolize, to swallow alone (figuratively, to take all the wealth or benefit for oneself)

通人心 (tōng rén xīn) – to understand the heart and mind of others (to have insight into a person's thoughts or intentions)

强烈 (qiáng liè) – intense, strong

劝导 (quàn dǎo) – to persuade and guide

开杀戒 (kāi shā jiè) – to break the precept of not killing (in Buddhism)

The Switchman is a Buddhist

In the “The Buddha Speaks the Sūtra of Great and Vast Skillful Means. Volume Four”*, there is a story:

An Arhat went overseas to spread the Dharma and was traveling by ship with some merchants. There were 500 merchants on board, and one of them harbored an evil intention — he wanted to kill all his companions and seize all the wealth for himself. The Arhat, being able to read minds, knew that this man’s thoughts were strong and that it would be impossible to persuade him otherwise. So, the Arhat chose to break the precept against killing and killed him, saving everyone else.

*it is a machine translation of the sutra’s title; we did not find its official title online

阿罗汉不是怀着“功德”心,而是怀着“救人”的愿望去做选择的。星云大师在《生活与道德》中说:“山本玄峰禅师说:“一杀多生通于禅。”意思是:杀了一个人,因此而救了许多人,是通于佛法的。”

星云大师还说,在修行菩萨道时,除了动机要纯正,抱持大慈悲心之外,还要具备心甘情愿接受因果制裁的胆识,因为有所造作,必有报应。佛家讲究发愿,只要动机是利他的、慈悲的,并愿意承担因果报应,就是功德。

怀着 (huái zhe) – to carry in one's heart, to harbor (a feeling or intention)

功德心 (gōng dé xīn) – heart/mind of merit (intention driven by merit or spiritual benefit)

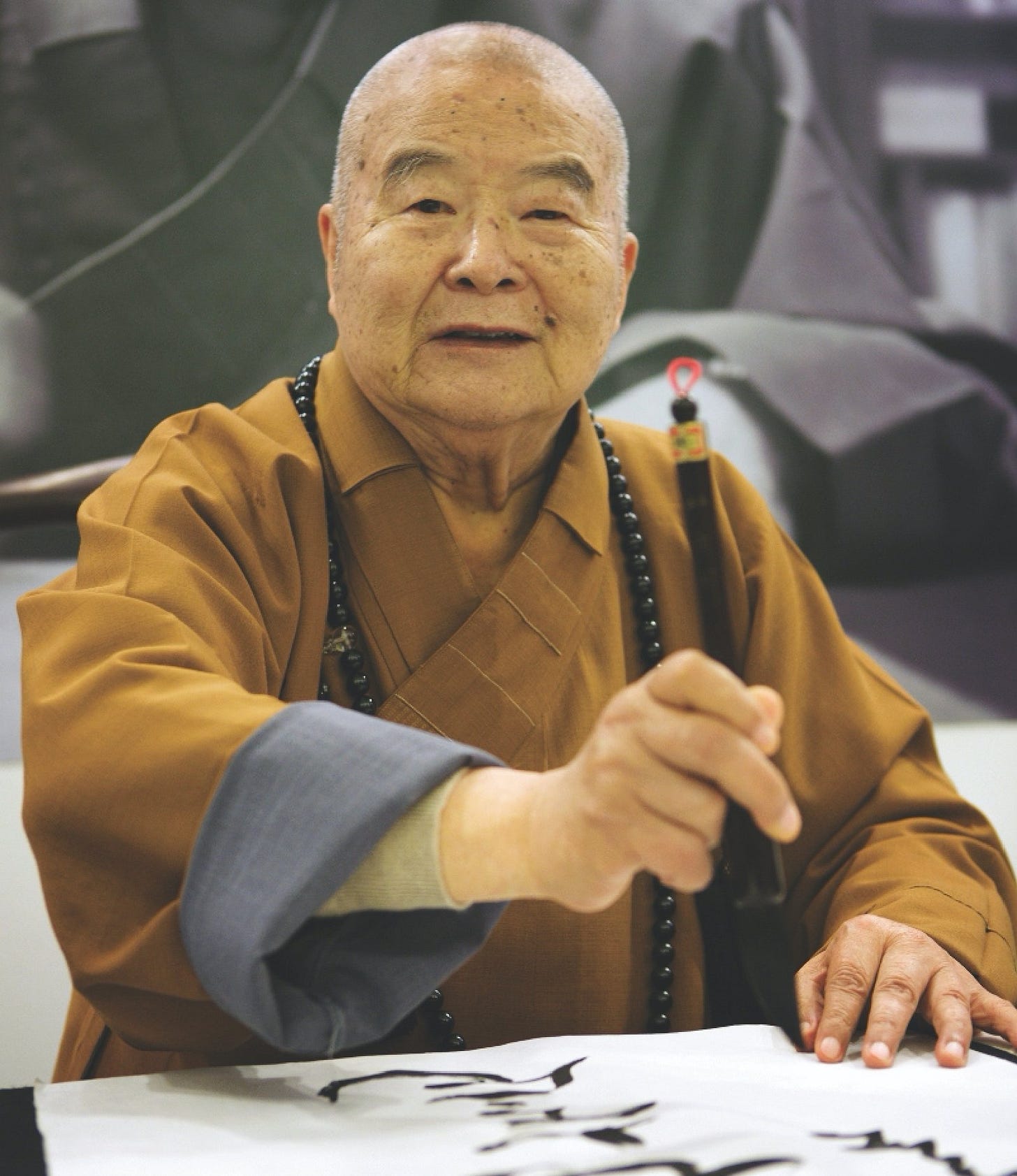

星云大师 (xīng yún dà shī) – Master Hsing Yun (a well-known Buddhist monk)

山本玄峰禅师 (shān běn xuán fēng chán shī) – Master Gempō Yamamoto (a Zen Buddhist teacher, quoted by Hsing Yun)

一杀多生 (yī shā duō shēng) – to kill one to save many

通于禅 (tōng yú chán) – in line with Zen (practice or teachings of Zen Buddhism)

动机 (dòng jī) – motivation, reason for action

纯正 (chún zhèng) – pure, righteous, correct

大慈悲心 (dà cí bēi xīn) – great compassion, deep compassion

心甘情愿 (xīn gān qíng yuàn) – to be willing, to consent with all one’s heart

因果制裁 (yīn guǒ zhì cái) – karmic retribution (the consequences based on one’s actions)

胆识 (dǎn shí) – courage and wisdom

有所造作 (yǒu suǒ zào zuò) – to perform actions, to engage in deeds

报应 (bào yìng) – karmic retribution

发愿 (fā yuàn) – to make a vow, to set an intention (often in a spiritual context)

利他 (lì tā) – altruism, benefiting others

The Arhat did not act with the desire for merit, but rather out of a genuine wish to save others. In “Life and Morality”, Master Hsing Yun wrote:

“Zen Master Genpō Yamamoto said: ‘Killing one to save many aligns with Zen.’”

This means: killing one person in order to save many is consistent with Buddhist principles.

Master Hsing Yun also stated that when practicing the Bodhisattva path, in addition to having pure motivation and great compassion, one must also have the courage to willingly accept karmic consequences, because any action inevitably brings results. In Buddhism, vows are important — as long as the intention is altruistic and compassionate, and one is willing to accept the karmic outcomes, it is considered meritorious.

于是,这位意志坚定的佛家徒扳道工可能选择“非暴力不合作”,脱下工作服,扳道从此与他无关,然后开始念经超度。更极端的佛教徒,可能会坐在铁轨旁边自焚,表达自己对电车系统的抗议。

意志坚定 (yì zhì jiān dìng) – strong will, firm determination

非暴力不合作 (fēi bào lì bù hé zuò) – non-violent non-cooperation (a principle of non-violence and passive resistance)

念经 (niàn jīng) – to chant scriptures, recite sutras

超度 (chāo dù) – to help spirits transcend, to guide them to peace (often refers to a Buddhist ritual for deceased souls)

自焚 (zì fén) – self-immolation, to set oneself on fire as a form of protest

Thus, this resolute Buddhist switchman might choose “nonviolent resistance”, take off his work uniform, and refuse to touch the switch — and instead start chanting sutras to help guide the spirits. A more extreme Buddhist might even self-immolate by the tracks as a protest against the trolley system.

二、扳道工是儒教徒

安史之乱时张巡固守睢阳,城破被执,骂贼而死,乱后廷议封赠,对张巡的评价有争论。

因为张巡守城时粮草断绝,连老鼠都吃光了。张巡杀死自己的妾,把她的肉分给将士们吃。后来守军干脆以人为食,吃尽妇女老幼三万人。城破时,百姓只剩下四百余人。对此,大儒王夫之的评断:

“张巡捐生殉国,…., 其忠烈功绩,......,国家崇节报功,自有恒典,诎之者非也,议者为已苛矣。虽然,其食人也,不谓之不仁也不可。”

安史之乱 (Ān Shǐ zhī luàn) – An Lushan Rebellion (755–763 CE)

张巡 (Zhāng Xún) – Zhang Xun (a general of the Tang dynasty)

固守 (gù shǒu) – to hold fast to (a city, position); to defend stubbornly

睢阳 (Suīyáng) – Suiyang (a historical city in present-day Henan Province)

城破 (chéng pò) – fall of a city

被执 (bèi zhí) – to be captured

骂贼而死 (mà zéi ér sǐ) – to die cursing the enemy

廷议 (tíng yì) – court debate or discussion (among officials/emperor)

封赠 (fēng zèng) – to confer titles or honors (usually posthumously)

粮草断绝 (liáng cǎo duàn jué) – supply lines cut off; food and fodder exhausted

妾 (qiè) - a historical Chinese term that means concubine

将士 (jiàng shì) – officers and soldiers

干脆 (gān cuì) – simply, just (often bluntly or decisively)

以人为食 (yǐ rén wéi shí) – to resort to cannibalism

妇女老幼 (fù nǚ lǎo yòu) – women, the elderly, and children

百姓 (bǎi xìng) – common people

大儒 (dà rú) – great Confucian scholar

王夫之 (Wáng Fūzhī) – Wang Fuzhi (a prominent late-Ming/early-Qing Confucian thinker)

捐生殉国 (juān shēng xùn guó) – to sacrifice one’s life for the country

忠烈 (zhōng liè) – loyal and heroic

功绩 (gōng jì) – merits and achievements

崇节报功 (chóng jié bào gōng) – to honor integrity and reward service

恒典 (héng diǎn) – established custom or enduring tradition

诎之者非也 (qū zhī zhě fēi yě) – those who belittle him are in the wrong (literary style)

议者为已苛矣 (yì zhě wéi yǐ kē yǐ) – the critics were being too harsh (classical phrasing)

不谓之不仁也不可 (bù wèi zhī bù rén yě bù kě) – it cannot be said that it was not unkind; he failed in benevolence

The Switchman is a Confucian

During the An Lushan Rebellion, Zhang Xun resolutely defended the city of Suiyang. When the city finally fell, he was captured and executed after cursing his enemies. After the rebellion, the court debated how to posthumously honor him. Zhang Xun's legacy was controversial.

Why? Because during the siege, the city ran out of food — even rats were eaten. Zhang Xun killed his own concubine and distributed her flesh to the soldiers. Eventually, the troops turned to full cannibalism, consuming some 30,000 elderly, women and children. By the time the city was breached, only around 400 civilians remained. The great Confucian scholar Wang Fuzhi commented on this:

“Zhang Xun gave his life for his country …— his loyal and heroic service is unquestionable... The state has long-established traditions of honoring such virtue and merit. To deny him that is unjust, and those who criticize him are too harsh.

That said, his act of cannibalism cannot be called benevolent (ren).”

所以,在电车难题中选择干掉一个或者干掉五个,对儒教子弟来说,最终都不算事情上的成功。论语中有句谚语:不成功,便成仁。既然事情上无法成功,那就求仁。

何为仁?

子曰:“夫仁者,己欲立而立人,己欲达而达人”,“己所不欲,勿施于人。” 面对电车难题时,上面这两项关于“仁”的定义也是两难的,没办法提供标准答案。左边的一个是人,不能被轧死,右边的五个也是人,也不能被轧死。

干掉 (gàn diào) – (colloquial) to kill, get rid of

子弟 (zǐ dì) – disciples, followers (here: Confucian followers)

论语 (Lún Yǔ) – The Analects (Confucian text)

谚语 (yàn yǔ) – proverb

不成功,便成仁 (bù chéng gōng, biàn chéng rén) – if one doesn’t succeed, one should at least act virtuously (either success or moral integrity)

求仁 (qiú rén) – to seek benevolence/virtue (仁)

子曰 (zǐ yuē) – “Confucius said...” (classical phrase from Analects)

己欲立而立人 (jǐ yù lì ér lì rén) – one who wishes to establish himself also helps others to establish themselves

己欲达而达人 (jǐ yù dá ér dá rén) – one who wishes to succeed helps others succeed

己所不欲,勿施于人 (jǐ suǒ bù yù, wù shī yú rén) – do not impose on others what you yourself do not desire

两难 (liǎng nán) – dilemma

So, when it comes to the trolley problem — choosing to kill one or five — for a Confucian disciple, neither counts as a true success. The Analects contains a saying:

“If you cannot succeed, at least attain ren (benevolence).”

What is ren?

Confucius said:

“A benevolent person helps others to stand when he wants to stand himself; helps others to succeed when he wants to succeed himself.”

“Do not do to others what you do not wish for yourself.”

In the face of the trolley problem, these two definitions of ren create a moral dilemma — they offer no clear answer. The person on the left is human and shouldn’t be killed; the five on the right are also human and likewise shouldn’t be killed.

那该怎么办呢?仁的含义,对不同的人,是有内在差别的。儒家的仁有等级秩序,按照“亲亲”的逻辑逐渐从高到低往下排列的:自己、父母、兄弟、朋友、熟人、国人、外国人。

后来的三纲五常、四维八德把这种差别和秩序作为儒教规范固定下来。所以,干掉一个还是干掉五个,取决于这位儒教扳道工心中的“仁”的排列秩序。

含义 (hán yì) – meaning, implication

内在差别 (nèi zài chā bié) – internal difference, inherent distinction

等级秩序 (děng jí zhì xù) – hierarchical order

亲亲 (qīn qīn) – (Confucian term) the principle of favoring kin; familial affection

三纲五常 (sān gāng wǔ cháng) – the Three Cardinal Guides and Five Constant Virtues (Confucian ethics)

四维八德 (sì wéi bā dé) – Four Principles and Eight Virtues (Confucian moral concepts)

取决于 (qǔ jué yú) – to depend on

So what should be done? The meaning of ren differs subtly between individuals. In Confucianism, ren follows a graded hierarchy — it is ordered according to the logic of kinship closeness: starting from oneself, to parents, siblings, friends, acquaintances, fellow countrymen, and finally foreigners.

Therefore, whether to sacrifice one or five depends on the switchman’s personal hierarchy of ren.

三、扳道工是道家弟子

杨朱算大半个道教,“一毛不拔”是关于他的成语。

“拔一毫而利天下,不为也。”

他的意思是,任何无辜的个体的利益都不能伤害。损己利人的事情不做,损人利己的事情更不能做。“悉天下而奉一身,不取也。”

一个也不能杀,五个也不能杀。显然,如果杨朱被迫当这个扳道工,逃跑是他的唯一选择。

杨朱之前的老子就是如此选择的。春秋末年,天下大乱,老子弃官,骑青牛西行,归隐老君山。

在道家的逻辑中,不应该发生电车难题。

杨朱 (Yáng Zhū) – Yang Zhu (early Chinese philosopher associated with proto-Daoism)

一毛不拔 (yì máo bù bá) – not even pluck a single hair (idiom: extremely selfish)

毫 (háo) – hair (fine or tiny, often symbolic of smallness)

利天下 (lì tiān xià) – benefit the whole world

不为也 (bù wéi yě) – would not do it (classical phrasing)

无辜 (wú gū) – innocent, blameless

损己利人 (sǔn jǐ lì rén) – harm oneself to benefit others

损人利己 (sǔn rén lì jǐ) – harm others to benefit oneself

悉天下而奉一身 (xī tiān xià ér fèng yī shēn) – to take everything from the world to serve oneself (classical phrase)

显然 (xiǎn rán) – obviously, clearly

唯一选择 (wéi yī xuǎn zé) – the only choice

弃官 (qì guān) – to give up an official post

青牛 (qīng niú) – green/blue ox (mythical animal Laozi rode westward)

西行 (xī xíng) – to head west

归隐 (guī yǐn) – to retire into seclusion

老君山 (Lǎo Jūn Shān) – Mount Lao Jun (sacred Daoist mountain)

3. The Switchman is a Daoist

Yang Zhu is considered half a Daoist. The saying "一毛不拔" ("not pulling a single hair") is associated with him.

“If pulling a single hair benefits the world, I will not do it.”

His meaning is that the interests of any innocent individual cannot be harmed. He does not engage in actions that harm oneself to benefit others, nor does he engage in actions that harm others to benefit himself.

“To nourish the world while neglecting oneself is not acceptable.”

Neither one person nor five people should be killed.

Clearly, if Yang Zhu were forced to be the switchman, his only choice would be to run away. Laozi, who preceded Yang Zhu, made a similar choice. At the end of the Spring and Autumn period, when the world was in chaos, Laozi abandoned his official post, rode a green ox westward, and withdrew to the Laojun Mountain.

In Daoist logic, the trolley problem should not even occur.

What about you? What would you do?

Antoine & Dorota